The RISE and FALL Of Music Theory [Why Academic Music Theory Sucks]

Does music theory exist to make being a musician easier?

Or does it exist to give you lots of sophisticated, fancy-sounding words that you can use to impress all your friends with? (They aren’t as impressed as you think they are, by the way)

Whenever I start this way, I know somebody’s going to reply to this email with: “Oh, Tommaso, stop it with the rhetorical questions. Clearly, it’s to make being a musician easier!”

And that’s where you’d be wrong. It’s not a rhetorical question at all.

Indeed, it turns out that the music theory that is taught in many universities/jazz colleges/other ‘official’ institutions has been developed specifically to impress other people with big-sounding words.

“Wait, what?”

Yup, you heard me well.

What I have to tell today is a story that most people don’t want to hear.

Some people don’t want to hear that the theory they spent so much time learning does not help them make music.

Some people are just not interested in the story. I mean, who wants to watch a video on the history of music theory? Most guitarists instead go: “just tell me if I have to use my ring finger or my pinkie to fret that lick”…

Some people are suckers for “you don’t need to learn theory”. Of course they end up learning a poorly taught (and poorly thought) version of music theory anyway and then wonder why music does not make sense.

Some people are teaching music theory, and so they have a vested interest in not hearing this.

(Today is also the day I will make a name for myself as a conspiracy theorist, lol)

“But wait, Tommaso,” you’ll say, “You teach music theory too!”

Fair point - see, I did not say that all music theory is made to impress other people. If you want a slogan: some music theory sucks, but some doesn’t.

But if you want to know more about this, you will have to watch the video below… because at this point the story of how all this happened becomes important.

So… if you are one of the people who are genuinely curious about music theory and how we ended up with the crap “academic theory” most people teach today, and what the alternatives are… watch this video on the Rise and Fall of Music theory:

Speaking of practical music theory, one of the most important things you can do for yourself as a guitar player is memorize all the notes on the fretboard.

For many, this sounds impossible. But I can promise you that with just 5 minutes a day, you can memorize your entire fretboard in a few months. Check out my guide to learning the notes on your fretboard to see how.

Video Transcription

Hello, internet. So nice to see you. I got that great comment and I want you guys to listen to it.

I’m wondering if all this debate stems from a terminology problem theory sounds like it’s sort of removed from practice and as some sort of purely academic exercise, it also suggests a system of rules, which confuses people, for example, am I allowed to play this note in this key music patterns, on the other hand, communicates both immediate practice utility and space for academic exploration, and does this without communicating that certain other things are legal?

No to think that, for example, learning new drum patterns are turning you into feeling less robot. And I suspect that people would feel the same way about learning new, harmonic and melodic patterns. We’re about patterns. I mean, for example, perfect cadences don’t and substitutions and things like that.

These are great points. And you guys will be surprised to know that that’s exactly how music theory used to be. But not in modern times. When all these things started, when we started playing music and teaching music. That’s how music theory was it was stitching patterns. And then in modern times, everything fell apart.

And now we are stuck, in a sense with this kind of horrible music theory that most people teach. That seems to be cumbersome and full of rules, and full of prohibition and all this kind of thing. What happened? How did we get to this point? Well, let me tell you the story of the rise and fall of music theory. You don’t start don’t have time, but let’s get a bit closer to us or, to our time, it all starts in the 1700s.

During the Baroque era, when music theory was taught as music, there was no term music theory, there was no name music theory, music theory meant nothing. Everything we know as music theory, the notes, the intervals, the relationship counterpoint, etc, was taught as music. And he was part of a complete curriculum that contained both what we will call theory, and what we will call practice. But it was a unified thing, people were not separating that. Now, if you wanted to learn music in the 1700s, you had two possible choices.

You can learn music as a professional, or as an amateur. And I want to stress that amateur did not have at the time, any of the negative connotation that it has today. Amateurs were respected. Okay. It was just you had those two different paths. So if you wanted to be a professional, you had to start when you were a kid, or at least very young, there were a number of institutions, the most famous one were the conservatories.

In Naples, where essentially there were places where you put all the orphans, okay, a lot of people were dying at the time, for many different reasons, and a lot of orphans. And you were teaching those people who are teaching those kids music from a very early age, with the idea to make them musicians, musicians, for them meant everything meaning you’re able to compose, you’re able to improvise, you’re able to become a human jukebox, where you play music as a continuous stream out of you.

And you can keep playing and playing and improvising everything by yourself or in an ensemble. Okay, and you can also teach the whole package, okay? As a professional, the first three years of your instruction, when you were a kid, were spent only by singing, there was a great ear training a bit radical if you want them but they were not allowed to touch an instrument unless you had three solid year of singing under your belt.

And you could sing a number of things like scales or arpeggios, etc, etc. without even blinking, okay, you learn to read music by singing it, not by playing okay. And it was grueling, but it worked. And then gradually they were teaching you patterns, okay?

And the patterns were very simple at the beginning, okay, started at the beginning of a teaching simple, you simply something like first chord, fifth chord, the first chord, what do we call the tonic dominant. And then we gradually making it more complex less to do with the suspension, so I Csus4, G, C again, and again, gradually making them more complex.

Okay, but now add, I add another point in between. And then okay, all these other code never learning these all over the keys, improvising melodies on top and on this kind of thing. And the whole thing was learning patterns exactly, like the comment at the beginning of the video set. That was for the professionals.

And when you learn all those patterns and learn to put them together, you have an immense vocabulary from which you can literally improvise, if anything, those guys were able to sit down and write symphonies in days, not not in years, okay? They were able to sit down and write write, write, write, arrange things for any kind of ensemble just using what they learned using those patterns.

Okay. And I’m not sure it would have Slightly different curriculum, they will start learning the pattern and do a little bit of a little bit less singing. And they were not being so gung holy, moving them throughout all the keys and combined them in this way. So they were still able to do something, but not have the amazing abilities that the professionals had, at the time. That how it was in the 1700s.

And again, nobody called it music theory, it was just music as it should be. Because learning all this pattern is just music from teaching the the pentatonic scale today. But if I’m teaching you the circle of fifths, or any kind of chord progression, jazz, pop blues, whatever, it’s not theory, it’s what you actually do to make music you need to know it, period. Okay?

Doesn’t. It’s not this, this super big theoretical thing that you never use, it’s practical stuff. That’s the way it was, then everything changed, okay, then the scene of the museum in the musical scene changed. There are a number of reasons for that.

I’m not an historian. And even if I was, it’s long to explain all the economic changes between the 17, the 1700s, and the 1800. But everything changed. And musicians were not playing in courts anymore. They were, they were pretty much their own business, and whole tradition of teaching changed.

And so what happened is that there was still demand for professionals. But it was less people wanted to go to the whole course of becoming a professional musician, because it was grueling to go through all the singing and playing the patterns, and combine them fun after a certain point, but not for 10 hours a day, okay. And the amateur market changes still, and people start to be less interested in playing music.

But they become more interested in analyzing music and talking about music. So we have the rise of a different class like musicians, composing for bigger orchestras that you cannot play on your piano at home. And that is less interested in playing this thing at home, there’s more interest in going into the concert and having a conversation about that. This is also the period when the university start to build up in Europe.

So we started out the first university, the first university started in the 1500s. But this started to become common in the 1800s. And so the first music courses were not surprisingly made to create professional musicians. The first secondary post secondary music courses, so University College music courses, were not made for people to become professional musicians. There were some courses that will help to help you make becoming a professional musician.

But you couldn’t graduate without knowing nearly anything about how to compose, and nuclear graduate taking all the courses that allow you to talk about music, analyze music, and become a good music critic. It’s not surprising, if you think about it, that today, we are still in the same situation.

I know a number of people who graduate from the university or from colleges, and they know very little about making music, very little about actual theory and practical and political tradition of theory. But they can talk very expertly, and they’re very good music critics, there is nothing wrong with that. And I know that just by saying these on YouTube, I’m going to have a lot of haters. I don’t care.

That’s the situation right now, at this point, we started talking about music theory, because when you want to study and creative, what other people are doing, you want to distinguish between the executions of music practice and the composition. So music theory, and so will we invented all those things about how to analyze music. So all these things about tonic sub dominant and dominant chord comes up in this period, all the analysis, okay, or how to exactly name the chords.

And also all the idea of analyzing everything in chords and chord progression, come up in this period. Well, most musicians at the time, but not thinking of chords or chord progression ever, mostly thinking, melodies and other kinds of patterns. Okay, so we have all these thing it was invented for music critics, and gradually became the music theory we have today. No wonder that we cannot apply it to create music.

But the original music theory is still there. It’s very similar. It uses the same names. It’s just taught in a different way. When we talk about music theory, today, we’re talking about two different things. We’re talking about the original practice of music and all the patterns you can study to become better Okay, and every musicians knows patterns.

Whether you’re a blues player playing the pentatonic over a blues chord progression, or a jazz player playing modes over go over chord progressions, or you are you improvise in different ways you’re a rock musician in no power chords are all patterns that help you make the music you want to make and there is this, but music theory also referred to all the other theories, which could be interesting in themselves.

And it may be they also have to make some very specific kinds of music, but they aren’t didn’t have the kind of general applicability, or they’re less practical than other music than the original music theory. So if you learn want to learn of the set theory of music, or you want to learn all the new Riemannian relationship between chords, etc, you can, it’s interesting, but it doesn’t, it helps you analyzing a piece of music, it helps you much less in actually composing this piece of music, and it helps you practically zero in improvising and making music in real time. I’m not saying there is no value in this thing.

So I know I’m gonna have some people commenting, I’m studying this super theoretical thing, and they find it useful. I’m sure you do, the vast majority of the public looks at music theory and goes like, that’s useless. And they are right.

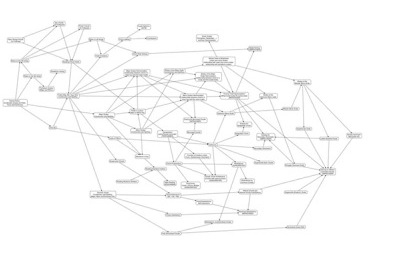

And they are completely right. That’s the point. What I’m trying to do in this channel, and in my course, in my website, etc, is to teach you the real applicable music theory because honestly, that’s what I’m interested in. I’m not interested in big theoretical constructions and geometry, sacred geometry of music and other stuff. It could be interesting, it’s very aesthetic and makes for nice diagrams. But I’m interested in actually making music.

And that’s the theory I teach. And that’s the history of it originally was exactly that. Teaching patterns, learning patterns, putting them to practice, you guys can do whatever you want. If you want to become a musician, study this thing and make you become a musician. If you want to talk about music and analyze, there is value in that.

Study that that thing, but be clear on what you want to become, and do not mix those things. I am a guitar player. This channel is called music theory for guitar. My audience is always guitar player, my point of view is always how we make music on this instrument. And the thing I see that stops most people the biggest waste of time, the biggest bottleneck Okay, in your performance, I found is knowing where all the notes are on the guitar fretboard because unlike a piano, we don’t have black and white keys.

Okay, so we need to learn what the notes are, it seems impossible until you do it. If you don’t know how to do it, if you want help if you want to invest five minutes a day for just for just a couple of months, two or three months, and learn all the notes of your guitar permanently with instant recall. So it’s not a problem anymore. I created a system and you can find it in video and ebook format on the link on the top right.

It’s completely free. Go there, download it learning get better at playing guitar, knowing what the notes are. It’s super practical. It allows you to communicate faster with any other kind of musician and the supercharges your playing learn them get better learn the real music theory, become a better musician. This is Tommaso Zillio for MusicTheoryForGuitar.com and until next time, enjoy.