THIS Auditory ILLUSION Is Why Augmented Triads Sound DISSONANT

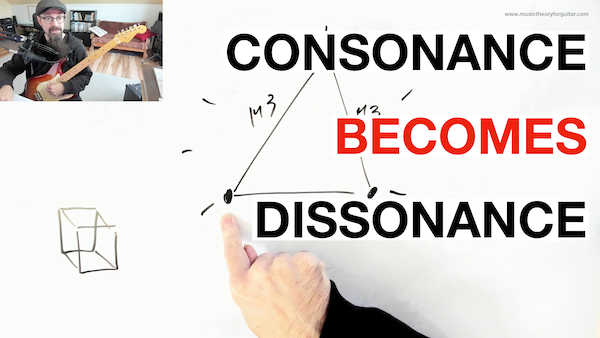

An augmented triad is made of a stack or major thirds. Which are consonant intervals.

And yet the augmented triad sounds dissonant.

Isn’t it a little bit weird? For a chord built exclusively out of an extremely pleasant and consonant sounding interval, it sure does sound unpleasant and dissonant.

What gives? How can this be true? Major thirds sound so good on their own but by playing more of them, they sound worse?

As we all know, too much of a good thing has not ever been an issue historically. Not even once.

If something sounds good, tastes good, or feels good, we all know that we should be maximizing our exposure to that thing as much as physically possible. It will be fine! Nothing ever goes wrong...

...yet, in this one single instance in the whole history of humanity, adding more of a good thing (major thirds) takes away from what made it good to begin with.

... well, that's not the actual reason. The reason augmented triads sound so dissonant is actually much more interesting than you might think.

The reason is that there is an auditive illusion that happens in your brain when you hear an augmented triad, that makes it seem to be dissonant even if it shouldn’t be.

How does this illusion work?

That is exactly the question that I will be answering in the video below:

Want to learn more about consonance, dissonance, and everything else there is to know about chords? Check out my Complete Chord Mastery guitar course which will teach you everything you need to know about chords and harmony on the guitar!

Video Transcription

Hello internet, so nice to see you! Why augmented chords are dissonant? They shouldn't be, but they are. Why they shouldn't be? Well, let me write down the notes of a C augmented chord and you'll see immediately that it shouldn't be much dissonant.

A C augmented chord is usually written as C, E, G sharp. Okay, so you are seeing the note between C and E, that the interval between C and E is a major third, and major thirds are perfectly consonant.

If I play a major third... Let me reset your ear after C, getting an electric chord, and then play C and E. It's a perfectly pleasant interval. It's consonant. Between E and G sharp... Well, E and G sharp, it's a major third.

We just see that the major third is consonant, so it's consonant here too. And plastic. And then if we go from G sharp to C... Well, you know that G sharp and A flat are the exact same note, meaning that in harmonics there are two names for the same frequency, right?

And if I go from A flat to C, guess what? It's another major third, which again, it's consonant. And indeed, if I play every pair of those notes separately, okay, which I'm going to do right now, I'm playing any pair of those notes separately, let me get back in camera, that's not going to sound fine.

So C and E sounds consonant, okay? I have to, by the way, reset your ear after doing that, because I don't want you to think of the previous interval. So I'm going to do that, and then I'm going to play these.

Good. Now I'm going to play E and G sharp. Okay, and that sounds perfect. perfectly consonant, now let me play something good, and I'm gonna play G sharp or A flat and C, which I can play it this way, but I can invert them, and that's like in a perfectly pleasant interval.

So pairwise, those notes are all consonant. So why, when I put them together, they sound like a fire alarm, okay? Right? Well, it's clear that somehow the dissonance is in your mind, because again, those two notes are not consonant, not dissonant, those two notes are consonant, not dissonant, those two notes are consonant, not dissonant, those two notes are consonant, not dissonance, okay?

But when I play all three of them, they sound dissonant, so which means that The dissonance is not due to the frequency ratio of those, like lots of people say, and I made a video about that, which you can find on my channel.

The dissonance is not due to the frequency ratio, it's due to something else. And indeed, the dissonance is in your brain. So what's happening in your brain? Well, you see, your brain is trying to make sense of this.

Okay? And your brain has essentially one possible way to make sense of the sound. Something that your brain does all the time, when you play a sound to it, something that your brain keeps doing all the time when you listen to music, and you're not conscious of that, because it's done automatically in the background, is that your ear is trying to make sense of the sound.

And the way to make sense of the sound is to find a root note, and then think of all the other notes in relationship to that root. So if you're hearing... ...a chord progression, your brain, after hearing that, knows that...

...C is the tonic chord, and the C note is the tonic key, because what you're doing here, you are playing C major, F major, G major, C, which are I, IV, V in the key of C. And for some reason, your brain knows what a major scale is, and when your ear hears all that, it recognizes this note as the tonic, as the root of everything, and then it relates all the other notes to that.

So when you come back to C, you are coming back home, you're coming back to the main note, and the song is finished. Your ear does that automatically. You don't have to think about it, okay? And how do your ear does that?

Let me show you. Your ear does that by thinking of... the notes that there are in the chromatic scale okay which there are 12 notes in the chromatic scale as you know and I'm gonna put them on a clock okay starting from C C D E F G A B and all the notes in between you know C sharp D flat D sharp A E E flat F sharp G flat G sharp A flat and then A sharp B flat when you play a C major chord for instance you're playing the note here the note here and the note here this is not a symmetric shape there is a major third here there is a minor third here there is a perfect fifth here this asymmetry tells your ear where the root is.

It's a question of asymmetry, okay? Indeed, that has a lot to do with the difference between symmetry and order. For some reason people think that symmetry and order are the exact same thing, when in reality they are the opposite.

It's a strange thing to say, but that's how it is. Especially if you look, if you know something about science, mathematics, etc., that's the case. Asymmetry is when you have an object, okay, or something, and you change it in some way, but the object is still the same.

For instance, this marker, it's a cylinder. If I don't look at the paintings at the label on top, and if I just turn it, it's the same mark. Even if you look at the label, if I turn this 180°, it looks the same, right?

So the marker is symmetric, okay? I change something and it's still the same, okay? If any kind of object has a symmetry, there's always something that you can do to change it, you can rotate it, you can flip it, you can do something, and the object is still the same.

That's what symmetry is. Order is the exact opposite. Order is when you have an object and there is no way to transform it, change it, so that it's the same, okay? What do I mean? Let's take this board.

If this board is completely white, just by looking at the board with no markings on top, you cannot tell which way is up and which way is down. If I flip the camera, the board will look the same. If I flip the camera upside down and still point at the board, you cannot tell if the board is upside down or not.

It's completely white, it's symmetric. If I point the camera to a mirror, you cannot tell you're seeing the whiteboard to a mirror because there are no markings on the whiteboard. The board is perfectly symmetric.

The moment I write something on the board, like this side up, now I've ordered the board. Now you know that this side is up, if I flip the camera around or if I put this camera through a mirror, now you can tell, okay, always this side is up, and you will see this right thing mirrored, and so you can recognize you're looking at the camera through a mirror.

I've ordered the board, I've destroyed the symmetry. the board is not symmetric anymore, now this is up, it's not symmetric with the down, now this is right, it's not symmetric with the left, okay? Order and symmetry are opposite.

Why am I doing all this philosophical discussion? Because see here, that's the thing, when you have again a major chord like the C major chord and you have the notes C, E, G, C would be here again, E would be here, G would be here, this shape is not symmetric, that's a major third, that's a minor third, that's a perfect fourth.

Since it's not symmetric, your ear can tell that one of the notes is more special than the other, which is the root, okay, and can pick a root. The algorithm in which that your brain uses to do that, it's a fairly complicated, but at the end of the day it picks one note as the special one, that is fantastic.

It works, but now what happens when you play to your brain an augmented chord? The augmented chord is made by the note C which is here, E which is here, and G sharp which is here, and what happens is that you have a major third here, a major third here, a major third here, the structure is symmetric.

So your brain could pick equally well this note or this note or this note as the root, because since there is a symmetry the shape is not ordered, okay, you have three possible solutions for the root.

What happens to your brain, that's where the problem happens, is that your brain gets confused, okay, exactly as if you couldn't tell up from down, exactly as it happens when you look at all those illusions.

You know those illusions where you have... Which of those two faces is in front? Is this face here in front? Or is this face here in front? And you're looking at this cube from below. You cannot tell, right?

This figure has two interpretations in your brain. It's symmetric in some way. There are two interpretations, so when you look at it, you can perceive this face to be in front, or you can perceive this face to be in front, but you cannot perceive both of them at the same time.

What happens to your hearing is that your brain is trying to perceive this as the root, and this as the root, and this as the root at the same time. It's a glitch in your hearing system. And so when you hear all those three at the same time, that confusion is perceived as dissonance.

The dissonance is not... that those two notes are dissonant, because they are consonant. It's not that those two notes are dissonant, because they are consonant. And it's not that those two notes are dissonant, because they are consonant.

Okay. It's when you play all three of them. Or you have in mind all three of them, okay? All the three of them together, since the shape is symmetric, prevent your brain to find one specific root. It's a problem, okay?

And that's why augmented chord sounds dissonant. That's the real reason. But we can use that, because symmetry is always a nice property, even in music. And indeed, you can use these kind of chords, the augmented chord, to change key, okay?

Because since they are symmetric, and since they have more than one root, when you play them, this destabilizes the perception of a tonic. So you can move the tonic from one note to another note, which is changing key, okay?

And I explore these and more ways to change key in my new course, Modulation Mastery. Okay, Modulation Mastery is a completely new revolutionary course, in which I'm explaining, and it works for both guitar players and piano player, and anybody else who can play chords, whether it's on an instrument or on the computer.

So if you use a DAW or MIDI or other things, if you do any of those things, you can take Modulation Mastery, and in this course, I'm explaining all the possible ways discovered so far in the history of music to change key.

We work on several different ideas, on more classical modulation, on jazzier modulation, on more modern modulation, on avant -garde modulation. We do chromatic modulation, we do sequence modulation, we do a number of different things, we do an harmonic modulation, we do a number of different things, we take different approaches, and we explore them, and we learn.

to write modulations, write changes of key that are emotional and that can serve your song. Because one of the problems that I see in every other course of signal modulation, in every other resource of signal modulation, is that they are trying to give you the fastest way to move from one key to another, and where's the fun in that?

You don't want that, you don't want to move from one key to another, you want to really milk all the emotion that comes from moving from one key to another and make a modulation that is exactly as long, exactly as emotional, exactly as dramatic as your song is needing right now.

And that's exactly what we do in this course, Modulation Mastery. Have a look at this link, if you go to this link, you're going to find a short video where I'm playing you a few modulations, and you can tell me if you like them or not.

And if you like them, I totally recommend you take the course. This is Tommaso Zillio for musictheoryforguitar.com, check out Modulation Mastery and until next time, enjoy!