THIRD Inversion Is The BEST Inversion (For A 7th Chord)

Do you know what most often generates an emotional response in music?

There can of course be many things that do this, but there is one musical concept that accomplishes this more often and more effectively than anything else.

This concept, of course, is:

Bass Solos

...

...

No, no, hear me out, it will make sense... See:

there is no emotion more powerful than righteous anger...

... and there is nothing in this world more infuriating than a great song being ruined because the bass player just needed to have their special little moment.

...

... with this being said, a very very close second place for "what generates most emotions in music" is the concept of Tension and Release.

Indeed, other than bass solos, tension and release is the primary way of making a listener feel an emotional response to music.

And unlike bass solos, tension and release can create a wide array of emotions (whereas bass solos can create only rage!)

But there’s a problem.

In order to effectively use tension and release in your music, you need to know what you’re doing.

Luckily, developing this understanding isn’t the most difficult thing in the world.

In the video below, I’ll show you a relatively tense chord (that you may not have even seen before!), and I’ll show you exactly how that tension should be approached and resolved.

More than that, I will show you how to create this tense chord simply by flipping around a few notes starting from a basic chord you probably know already.

And best of all, I will show you how that tension and release can work in your music, so you can use it, today, in your songs:

P.S. And all this for the small small price of... well, nothing. This one is a freebie - I want you to learn this so you won't have to rely on writing yet another bass solo...

Still have trouble with managing tension and release in your chord progressions? Check out my Complete Chord Mastery guitar course if you want to get better at writing chord progressions that flow nicely.

Video Transcription

Hello Internet, so nice to see you! today I want to talk about 3rd inversion chord, which is a very complex name for something super simple, and then just use a couple of them in what I was playing. And those chords are relatively unknown, I mean some people of course know them, if you went through a course of music theory, basic harmony, you probably know them, but most people don't because they never went through this course.

Okay, and it's kind of an hidden gem of music theory. So let's work, let's learn this 3rd inversion chord. On principle they are super simple, they are just 7th chords, okay, it could be dominant 7, major 7, minor 7th, okay, or even minor 7th flat 5, but any kind of 7th chord, and what the 3rd inversion means that we take the notes that is the 7th of the chord and we put them at the bass.

So we play them, we play the 7th as the lowest note of the chord, okay, so very simply it works this way, if I could, if I'm in the key of C, okay, I could take, as a first example, I could take a G7, okay, a G7 will have notes G, B, D and F, and I'm playing them in a slightly different order here, because it's easier to play on the guitar, because if I have to play G, B, D and F in order, it's kind of a stretchy one, but you can play them anyway.

G is the root, B is the 3rd, D is the 5th, F is the 7th, if we take the 7th and we play it at the bass, of course, I need to find a way to play it at the bass. Okay, but one way is this. It's just very simple one and then zero, zero, zero on string two, three and five.

So just that's one way, but I can also play it this way. The top three notes are the G major chord, the G, B and D, but the bottom note is the seventh. Okay, that's a third inversion chord. Super, super simple.

If I was doing this with another chord, and again, let's stay in the key of C. If I was doing this with the D minor seven, okay, D minor is D, F and A and the seventh is the C. Okay, of course, I can put them in different way.

If I put the C, which is the seventh at the bass and like playing something like that, so C, F, A, D. So F, A, D, or D, A, D, F, A is my D minor, C is the bass, which is the seventh of D minor. So as long as I put the seventh in the bass, I get a third inversion chord.

Simple as that. Now, how do those chords resolve? Meaning, how do they move? In general, they always come from the same situation and they always go to the same situation. So let's grab the whiteboard and see exactly what is happening here.

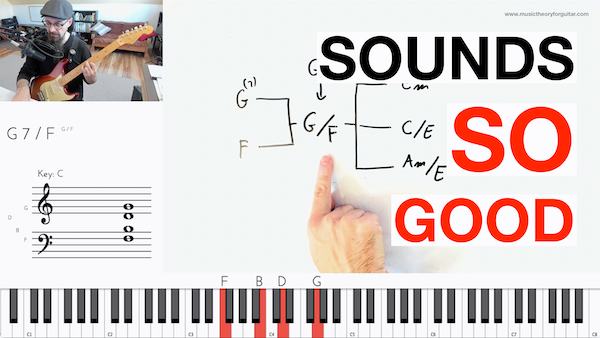

Practically, what happens is this. Okay, let me grab the other kind of whiteboard there. So let's say we have a third inversion chord. We take the G7. The third inversion chord is essentially G with a bass of F.

So top three notes are the notes of G, bottom note is the F. There are always the same two chords coming up before this and there are always the same three chords coming after this. So those are your options.

Before G over F, I can play a G. Meaning the same chord as the top. So that's a G with a bass of F. I'm playing the G just before. I could play a G7 too. Point is, in this case, it's in root position.

So either you play G in root position just before that or you play the chord built on the bass here. So you play F. Okay, why would you do that? Because this kind of ensures a smooth introduction for this chord.

So if I'm in a chord progression and I play, I don't know, C, then G. Oops, that was a big mistake. I'm playing C and then G. Okay, and then I'm playing G over F. Okay, and then I continue. You see that since I already have a G, I'm changing only the bass note.

And so, even if this chord is mildly dissonant, it doesn't sound super surprising or out of place. So essentially I'm introducing the top part of the chord, the G major, in here. Or I can come from F.

So I can play C major, F major, so you have to come in the F. That works because the bass is the same. In F, the bass is F. In G over F, the bass is still F, okay? So essentially I am either introducing the top part, so the G chord, or the bass, the F, before I play this chord.

Do I have to do this? No, as usually in music you can do whatever you want, okay? But that's a good way to introduce this chord and make it sound very, very natural, okay? Where does this chord go? Well, what's going to happen here is that the bass is always going to move down by step.

Okay, so if F is here, the three chords here will always have a bass of E. All the time, okay? And so, you could have three chords here. You could have the chord in the key of C, where the E is the root, which is E minor.

Or you can have the chord in the key of C, where E is the third, which is C. And again, I'm going to put E at the bass. And I can have the chord in the key of C, where E is the fifth, which is A minor.

And again, I'm going to put the bass of E. So again, let me recap why this happens, because the bass in this chord feels a strong push downward. Okay, so for most people, when they hear this chord, they feel that this F note has to go down a step in the scale.

One step below F, you have E. And so here, you can play any chord, as long as any chord that contains an E, any triad that contains an E, as long as you put this E in the bass. So for instance, I can have, again, G with the bass of F and then E minor.

And it works. Or G with the bass of F and then C with the bass of E. Or G with the bass of F and then A minor, which I will actually play it in a slightly different way like this. Okay, with this one, we're in typically the most foreign, okay, and this one the most natural, and this one will be surprising, but not too much.

Okay, that's the idea. If I change the chord here, if I put another chord, another third inversion, chord here, I'll have to do the whole thing again. So let me do this for now. Well, let me actually play a couple of progression contains of this.

So I could play C, then G. So now I'm here. G over F. Okay, and then E minor. See how it flows perfectly? Well, so I just did G, G over F, E minor. Or I can do the same. C, then G, G over F, C with the bass of E.

Okay, or C just to start, G major, G over F, and then add this E minor, the bass of E. I could put an E minor 7 with the bass of E. Okay, and it would probably work a little bit better. So C, G, G over F, A minor 7 with the bass of E, and then I can keep going wherever I want.

But I can come from F, so C, then F, G over F, maybe E minor, flows, okay, or C to start F, G over F, A minor, I'm gonna put A minor 7th with the bass of E. Okay, so the possibility if you use this chord here, but any chord in the key can be written in 3rd inversion.

So, let me take another one. Okay, what if I take D minor? Meaning D minor 7th. The 7th of D minor is C, so D minor with a bass of C will be our 3rd inversion chord. Yay, simple as that. Okay, and again it can come from two places.

The chord without the inversion, again the chord in root position, so simply D minor, or the chord with, the chord built on the bass of C. And you can go in three places. So, to see in what three places it can go, you take the C note, go down one step in the scale, C major, and you find the B note.

And then you write the chords that contain the triads that contain B. Okay, you will have the B diminished triad, which is usually playing instead B minor 7th flat 5. Okay, if you want to play it that way.

The diminished triad will always sound a bit meh, okay, in general, but it could work. Then we have the chord where B is the 3rd. If you think about it in the key of C major, if B is the 3rd, the chord.

is G major, so with the bass of B. That would be my preferred choice most of the time, by the way. Or you can find the chord where B is the fifth, which is E minor with a bass of B. And again, we could consider playing an E minor seventh.

Okay, so how do I play all that? Well, very simple. I am starting from C, and I'm getting into the minor with the bass of C. Okay, C, what notes I'm playing here. D, F, A. D, F, A, D. I don't know why the end is an extra A appearing in the transcription system.

Now, if I'm a guitar player, you may want to see me a bit closer, so let me change it this way. Okay, so C major is just this. Pretty simple, okay. D with the bass of C is three, three, two, three on the fourth central string of the guitar, okay.

Too crazy. And then again, I could go into Bm7b5, and why not, and then maybe later I can go to the minor 7, okay, or something else, or I can go Cmaj, Dm over C, G over B, great choice, sound just sounds good, and then maybe something else, C, okay, or from C, Dm over C, and then Em7 over B, okay, and then maybe A minor, I don't know, okay, point is, that's how the third inversion chord works most of the time, okay, now of course in music the sky is the limit, and the rules don't really apply all the time, those are just suggestions to make the thing work, okay, when you start learning, okay, or whenever you have situations where you want to use this chord, okay, you want to put this dissonance in your chord progressions, but okay, it doesn't flow well, etc.

So in this case look at that, because this is just a way to make it flow better, okay, it's kind of pointless in my opinion, okay, that's my opinion, and it seems that these lots of people disagree with that, but it's pointless for me to look only at the chord, okay, because music is movement, and so you want to see what typically comes before and what typically comes after, that's also why I teach in my courses, okay, it's good to know about the chord, good to know about the alteration, etc., but you have to see what comes before, what comes after, and how the whole things connect, okay, and that's how to use the third inversion chord, again, take any seventh chord, put the seventh at the base, now this is one use, but there are more advanced use, okay, but it's a super, can use the 3rd inversion chord to create key changes.

Okay, one example will be these, I'm just gonna, I'm just gonna play it. Okay, it's really not. I could start with C, F, maybe D minor. Actually, let me play it this other way. I play D minor. And then here, I'm going to put this, which is an E7 with a bass of D.

And then I'm going to resolve to A with a bass of C sharp. And then from here, I will do something like, okay, so I just create a modulation. on the key of C. I'm in the key of C. I could play the C, F, D minor, G7, D.

And maybe the second time, if I can F, D minor, I have the bass of D. So I can put in this E7 with the bass of D, which is the fifth chord in the key of A major. And then from there I can play this inversion, proving surprisingly difficult to play this inversion.

My fingers are not really good about that. Okay, so. And then second, fifth, one. And I just modulated very smoothly and very simply from C major to A major. Okay, that's just one example, okay? And so the third inversion chord can function in this way as a connection between two different keys.

That's just the simplest example, just the shortest modulation. And also, I don't really like short modulations. I like to dwell a little bit into the modulation and just extract all the emotion and all the tension I can from there.

So if you want to learn how to do that, okay, and we work also with the third inversion chords, of course, I have a new course. It's called Modulation Mastery, okay? It's here. And you can find the link down here right now.

And in this course, I'm teaching you all the possible known way to change key. And yes, all the possible known way. I did extensive research before writing this course. There are so many ways to change key that could be very short, very long, very dissonant, very consonant, very smooth, very angular, kind of lame.

or incredibly emotional, okay, and I'm showing you all those ways and they apply in all different situations, okay, there are ways of creating key changes that don't even require chords, they require only single note riffs, so if you're playing rock or metal, yeah, this course will do it for you, okay.

This course is appropriate for both guitar players and piano players, as you see there is always the piano roll under like I was doing right now, okay, or even if you just compose music at your computer, okay, as long as you can play chords one way or another, this course will work for you, okay, but again we go beyond just chords, and so we do the classical modulations, yes, we do the pop modulations, yes, and we go well well well well beyond that, straight into film music and other more complex kinds of music and see how they create key changes.

and how you can write those key changes with your instrument. So have a look at Modulation Mastery. This is Tommaso Zillio for musictheoryforguitar.com and until next time, enjoy.